1- Entangled Walls

Figure 1: 1/80 Plan of Lenné Triangle, 2022 and 1988 (Actual Size: 450mm × 450mm)

Lenné Triangle

Adjacent to Potsdamer Platz, located in the heart of Berlin, lies a place known as the Lenné Triangle. The 1/80 scale plan (Figure 1) shows the triangle in 1988 on the right side and in 2022 on the left side. Since the Wall collapsed in November 1989, the right side represents the year just before that historic event. In that year, large-scale protests erupted at the Lenné Triangle. Plans were announced to develop the lush, green triangle. Some people held up placards, while others set up tents and makeshift huts, protesting against the proposed development.

Now shift your gaze to the left side, to 2022. There, you see the cross-section of a modern building and a paved road. The once-vibrant green space, where the energy of the people swirled, was eventually swallowed by the tide of capital. It was transformed into a major commercial district packed with luxury hotels and the offices of top-tier companies.

When we hear that the Wall "divided East and West," do we unconsciously picture a boundary drawn mechanically along a fixed line? If you trace the trajectory of the Wall and the boundary line, you will notice that they are not perfectly aligned—they shift and waver slightly as they run through the city. This may seem like a minor tremor on the scale of Berlin as a whole. But at the same time, it represents a significant force that reshaped the forms and structures of human habitation and the environment.

This is not a sentimental story about urban development destroying nature. It is about a triangle of land whose very form and existence have been continuously rewritten by the Wall. Here, we will now attempt to capture the evolving landscape of this site.

Two Walls, One Space

Figure 2: 1/2000 Site Plan of Lenné Triangle, 1988 (Actual Size: 450mm × 450mm)

Let us take a broader view of the Lenné Triangle in 1988. Now shifting to a scale of 1/2000 (Figure 2), we can see the triangular plot floating at the center—that is the Lenné Triangle. But what immediately catches the eye is the massive red band boldly cutting across the site plan.

This is the Wall. By 1988, the Wall had undergone repeated evolutions to prevent escapes, and had reached a kind of final form. The red-marked area on the plan does not represent a single continuous physical wall. Instead, there were two parallel concrete walls, with an open shooting zone in between. This zone was heavily fortified with guard towers, anti-vehicle obstacles shaped like hedgehogs, and fences equipped with contact-sensitive sensors—traps designed to prevent escape. Even if an escapee managed to climb over the first wall, it would have been nearly impossible to reach the second wall unharmed.

By existing as two parallel walls—or in layered form—the Wall created a void of space between them, further increasing its lethal potential.

Entangled Path

So, how exactly did the Wall, which enclosed a void of space, run through Berlin? Let us consider the agency behind its construction.

The entity responsible for building the Wall was the East German government. Therefore, the Wall would not have been built within West Berlin territory. Construction would have taken place on the eastern side of the boundary. Strictly speaking, this means that the line of the Wall would not have been perfectly aligned "on top of" the East-West boundary, but rather would have followed it closely.

However, the Wall did not simply and obediently follow the boundary line. If you trace the Wall's curved path step by step ★1, you can identify several points where it deviates from the boundary (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Types of Entanglement (Black: West Berlin, White: East Germany, Red: Wall and Its Space)

It becomes clear that the Wall significantly diverged from the East-West boundary line at certain points. In other words, East Germany had essentially surrendered parts of its territory beyond the Wall while simultaneously absorbing the burden of hosting the physical barrier within its own territory. Why would they have allowed such a disadvantage? Perhaps they had no other choice.

Figure 4: Entanglement and Lakes/Rivers (Red: Wall and Its Space, Blue: Lakes/Rivers, Dashed Line: East-West Boundary)

For example, it would have been difficult to construct the Wall along boundary lines drawn over rivers or lakes. In such cases, the Wall was set back onto the eastern side of the land or diverted to places where bridges existed (Figure 4).

Furthermore, at the few crossing points that connected enclosed West Berlin with the outside world—namely checkpoints and train stations—the Wall exhibited even stranger behavior (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Entanglement and Passageways (Red: Wall and Its Space, Orange: Railways, Yellow: Roads, Dashed Line: East-West Boundary)

At checkpoints, facilities for checking and recording the identity of travelers were established. If such facilities were placed between two parallel walls, the Wall would bulge significantly eastward to accommodate them. In contrast, on roads and railway lines without major checkpoints, the Wall tended to thin out and follow the contours of the path. Additionally, in cases like Type e-10, the configuration of the Wall became highly complex—likely due to the peculiar conditions created by West Berlin's enclaves ★2.

When you shift your gaze from an aerial view to ground level, it becomes evident that the Wall was not aligned neatly along the boundary line. Constructing the Wall was not as simple as arranging blocks on a map. The East German government responded meticulously to the terrain and functional requirements, adapting the details of the Wall to prevent any outward leakage of its citizens. Seen on a map, these adjustments might appear almost comical in their improvisational nature. But when viewed from the ground, through the eyes of an individual standing before it, the Wall loomed as a disaster—advancing toward its surroundings and swallowing them whole.

Figure 6: Distribution of Entanglement

Lawless Lenné

The Wall deviated even at the Lenné Triangle. Here, construction ignored the natural undulations of the boundary line, resulting in a straight wall that caused part of East Berlin to jut into West Berlin (Figure 7). This created a triangular plot located west of the Wall but still belonging to East Berlin.

Figure 7: Entanglement at Lenné Triangle (Black: West Berlin, White: East Germany, Red: Wall and Its Space)

West Berlin had no authority to interfere with East German territory. Consequently, the isolated triangle became cut off from its surroundings, effectively turning into a lawless zone—a deserted island on land where human activity was limited. But for plants, it became an ideal environment for growth. Gradually, trees and vegetation flourished, and a biotope emerged. It is said that as many as 161 species of plants thrived in this secluded area.

This was not unique to the Lenné Triangle. Ironically, the death zone created by the Wall for East Berlin fostered rich green spaces on the western side. As time passed and the presence of the Wall became a familiar backdrop to life in West Berlin, these spaces were embraced by nature lovers, joggers, birdwatchers, nudists, and camping enthusiasts.

However, in the 1980s, attempts were made to rationalize the boundary lines, and negotiations over the sale and exchange of enclaves, including the Lenné Triangle, began to progress. At the time, West Berlin was planning to construct a highway along the Wall. On March 31, 1988, an agreement on the exchange of territory was reached between East and West Germany. West Germany agreed to pay 76 million Deutsche Marks (approximately 5.3 billion yen at today’s value), and East Germany agreed to transfer the territory on July 1 of that year.

This sparked outrage among West Berlin’s leftist groups. Environmentalists, punks, and autonomists launched fierce protests. Until the handover date, the West Berlin police were unable to intervene directly. Protesters began setting up tents and makeshift huts, occupying the triangle. Over time, the site turned into a small settlement. Even when tear gas was fired into the area, the occupiers stood their ground with unwavering resolve, refusing to leave.

Finally, in the early morning of July 1, 1988, the day of the handover, the West Berlin police launched a large-scale operation to clear the area. Nearly a thousand officers were deployed, supported by water cannons. The occupiers could not resist such overwhelming force. Instead, nearly 200 of them climbed over the Wall and "fled to the East”—a reversal of the usual escape pattern. This unusual event was widely reported as the first "defection" into a communist state. The East German authorities welcomed them. Border guards assisted the occupiers, providing them with breakfast in a cafeteria and even allowing them to return to West Berlin through the official border crossings with no repercussions ★3.

Modern Redevelopment

Figure 8: 1/2000 Site Plan of Lenné Triangle, 2022 (Actual Size: 450mm × 450mm)

In the 1/2000 site plan of 2022, the red-marked areas represent parts of the original Wall that still remain today. After the Wall collapsed in 1989, the reunification of East and West Germany outpaced the existing plans for highway construction. As a result, the Lenné Triangle became part of a redevelopment zone. The German government launched an urban design competition to transform the area adjacent to Potsdamer Platz into a central district that would link the eastern and western parts of Berlin.

The winning proposal was submitted by Hilmer & Sattler ★4. Their master plan envisioned a layered arrangement of high-rise buildings interspersed with open spaces. Multiple investors acquired sections of the development zone, and large-scale projects were carried out in line with the master plan. The key investors were Daimler-Benz, Sony, and ABB. The redevelopment project entered its execution phase in 1994 and reached substantial completion in 2004. Today, the area has become a major commercial district, home to luxury hotels such as The Ritz-Carlton and Marriott, as well as the offices of major tech companies.

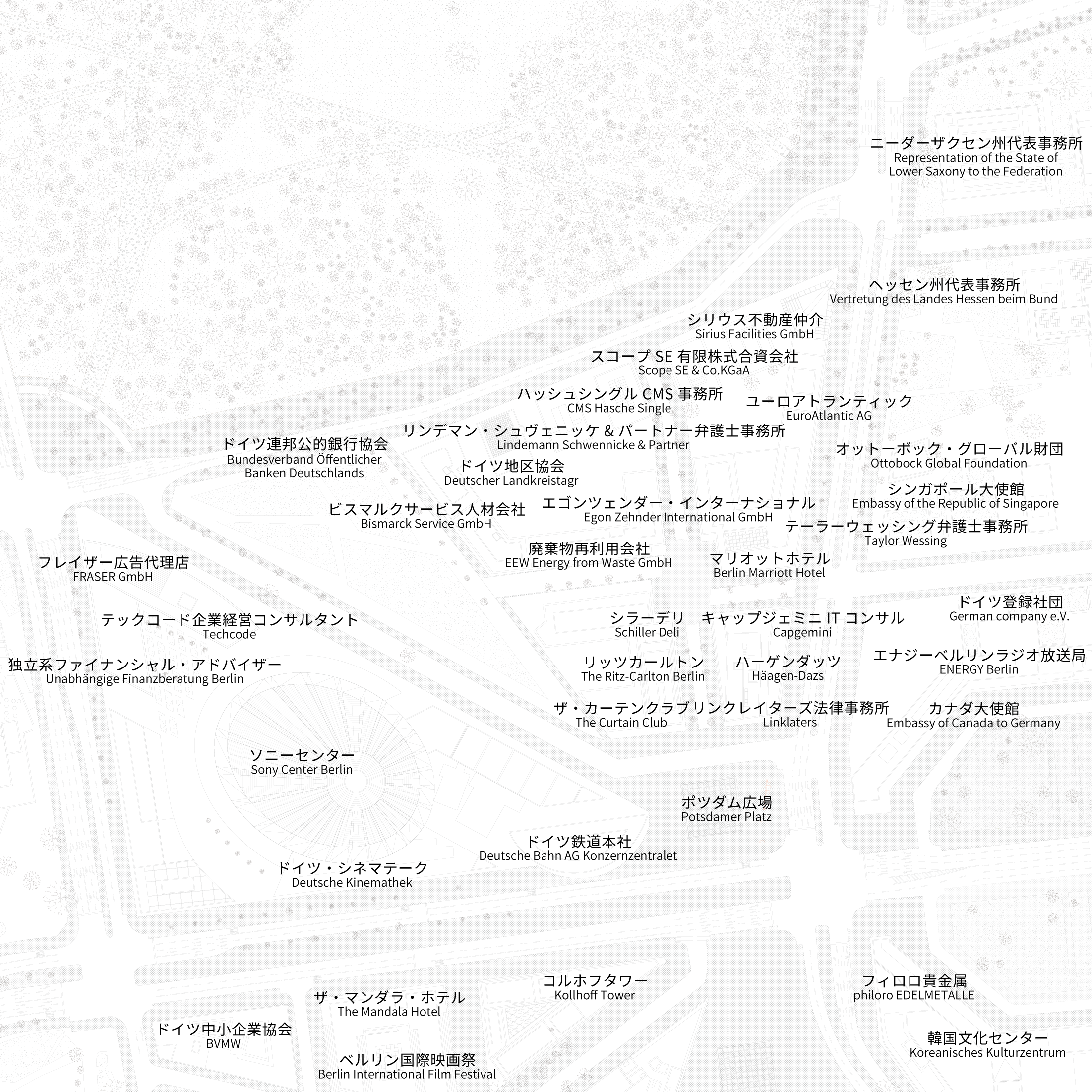

Figure 9: Facilities and Companies Around Lenné Triangle

The high-rise buildings shown on the right side of the 1/80 plan of 2022 ★5 were designed by Hans Kollhoff, a Berlin-based architect born in 1946. In addition to designing the Delbrück Bank building, Kollhoff also designed a high-rise known as the Kollhoff Tower on a site owned by Daimler-Benz. Incidentally, the master plan for that site was created by the architect Renzo Piano.

Both buildings feature modern facades clad in granite, with interiors finished in fine teakwood and terrazzo tiles. The facades of the lower floors are marked by prominent columns, while the middle floors are lined with rows of small rectangular windows. The stepped, terraced form of the upper section emphasizes the slenderness of the towers, presenting a refined design that embodies the grandeur of major corporations. Yet, despite their elegant lines, the narrow profiles and seemingly unstable tops of the towers create a lingering sense of unease—almost as if the buildings might collapse under the weight of their own rubble.

Or Perhaps Bicycles

The Wall gave rise to a lawless zone—an area abandoned by people that gradually transformed into a biotope for plants. This unexpected patch of urban greenery soon became a site of conflict between the administrative forces eager to develop the area and the public striving to preserve its rich natural environment. Yet when the Berlin Wall collapsed, the Lenné Triangle was swiftly handed over to large-scale capital interests.

The disordered trajectory of the Wall had created the unique environment of the Lenné Triangle—an ever-shifting landscape shaped by the interplay of East and West, government and citizens, plants and people, nation and capital. The site became a space of entanglement, where multiple forces continuously converged and collided.

The initial site plan is not just a layout of the Lenné Triangle; it is also a cross-section revealing layers of time accumulated within the space. What does this layered landscape tell us? Perhaps it speaks of a chaotic scene—an unstructured expanse of plants and makeshift huts set against the rigid, ordered presence of modern buildings. Or perhaps it suggests the image of bicycles scattered freely about, in stark contrast to motorcycles neatly confined within designated parking spaces.

6 June 2022 (translated on 20 March 2025)

Figure 1: 1/80 Plan of Lenné Triangle, 2022 and 1988 (Actual Size: 450mm × 450mm)

Figure 2: 1/2000 Site Plan of Lenné Triangle, 1988 (Actual Size: 450mm × 450mm)

Figure 8: 1/2000 Site Plan of Lenné Triangle, 2022 (Actual Size: 450mm × 450mm)

Notes

★1 — For the positional relationship between the Wall and the East-West boundary line, refer to the overview diagram of Berlin wall provided on the official Berlin website.

★2 — Type e-10 refers to Steinstücken, an exclave of West Germany. After the construction of the Wall, supplies to the exclave were delivered by helicopter until an agreement between East and West led to the establishment of a connecting corridor. This corridor was essentially a type of warp zone enclosed on both sides by high walls. For more details, see the website Steinstücken und seine Mauer — Geschichte und Ende einer Exklave zur Zeit des geteilten Berlins (Steinstücken and Its Wall — The History and End of an Exclave During the Era of Divided Berlin), which was created based on a dissertation submitted to the Berlin Institute of Technology in July 2011.

★3 — Regarding the protests, refer to the website of the non-profit organization Umbruch-Bildarchiv, which archives and makes available valuable photographs of leftist movements at the time. Footage of the protests can also be seen in the YouTube video Der Kampf um das Lenné-Dreieck (The Battle for the Lenné Triangle).

★4 — The overview of the competition proposal can be found on the website of Hilmer & Sattler.

★5 — The floor plans designed by Hans Kollhoff are documented in Hans Kollhoff, Hans Kollhoff en Helga Timmermann. Projecten voor Berlijn (Antwerpen: DeSingel, 1994). A summary is also available on the website of the Kollhoff Architectural Office.

Writers

Takafumi Tsukamoto, Akira Yamazaki

Draftsmen

Takashi Kawashima, Takafumi Tsukamoto, Akira Yamazaki